Dickens, Adaptation, and A Christmas Carol

My book manuscript is about children’s literature, the novel, and moral instruction. I argue that Victorian writers like Charles Dickens learned the narrative strategies that underlie their morally instructive novels from the stories they read as children. Chances are, this holiday season you’ll watch or read some version of one of the texts I write about: A Christmas Carol.

The novel is everywhere this time of year, in unexpected forms. Characters might be Muppets, or the Flintstones, or Barbie. Scrooge might be be Bill Murray as a television executive: Or Matthew McConaughey as a bachelor photographer:

Or Vanessa Williams:

Or Vanessa Williams:

All adaptations are interpretations. And even the oddest adaptations of A Christmas Carol might in fact be quite consistent with Dickens’s story, which is itself about interpretations, good and bad. Scrooge is initially skeptical about the instructive ghosts: when Marley asks him if he believes in ghosts, Scrooge says he can’t believe his own senses – “A slight disorder of the stomach makes them cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

But it only takes one visit for Scrooge to realize how valuable the lessons will be. When he meets the second ghost, he says, “I went forth last night on compulsion, and learned a valuable lesson. To-night, if you have aught to teach me, let me profit by it.” Before the story is half finished, Scrooge has already learned not only to recognize his own unhappiness but also to welcome future lessons.

By the third spirit’s visit Scrooge knows the game very well: he resolves “to treasure up every word he heard, and everything he saw.” The silent third spirit shows Scrooge a funeral, and Scrooge replies: “I see, I see. The case of this unhappy man might be my own. My life tends that way, now.” Scrooge is wrong. He incorrectly interprets his moral visions, failing to recognize himself in the “unhappy man.” When the truth finally dawns on him, he tells the spirit “hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse.” He is converted only after making that mistake.

Part of the lesson, then, is being wrong. To learn something from A Christmas Carol, we have to be willing to make a mistake – and then willing to correct it.

When we watch an adaptation of a novel, we typically ask, “how does this film compare to the book?” And we typically respond, “the book is better.” But A Christmas Carol gives us an opportunity. In Scrooge, Dickens shows us the power of being wrong. So when we look at an adaptation of A Christmas Carol, we can ask not just, “is it right in its interpretation” but also “how might it be different from the book, and what might that difference mean”? How might making Scrooge a television executive or a bachelor or a diva use Dickens’s novel to respond to modern, American cultural needs?

And if those responses turn us back to Dickens, is that such a bad thing? In Film Adaptation and Its Discontents, David Leitch calls A Christmas Carol “entry level Dickens”: people encounter the novel, often as children, and besides the moral lessons about compassion and conversion they gain the cultural knowledge that the story represents. The story provides an entry point not just to Dickens, but to adult culture more broadly (his reading of The Muppet Christmas Carol is especially good).

One problem: the story isn’t always associated with Dickens. Disney’s 2009 version, for example, advertises Jim Carrey and claims this is Disney’s A Christmas Carol — Dickens is nowhere on the poster.

One problem: the story isn’t always associated with Dickens. Disney’s 2009 version, for example, advertises Jim Carrey and claims this is Disney’s A Christmas Carol — Dickens is nowhere on the poster.

So at this time of year, maybe we need to be especially conscious that we make this connection: that we make A Christmas Carol entry-level Dickens rather than just another Disney product.

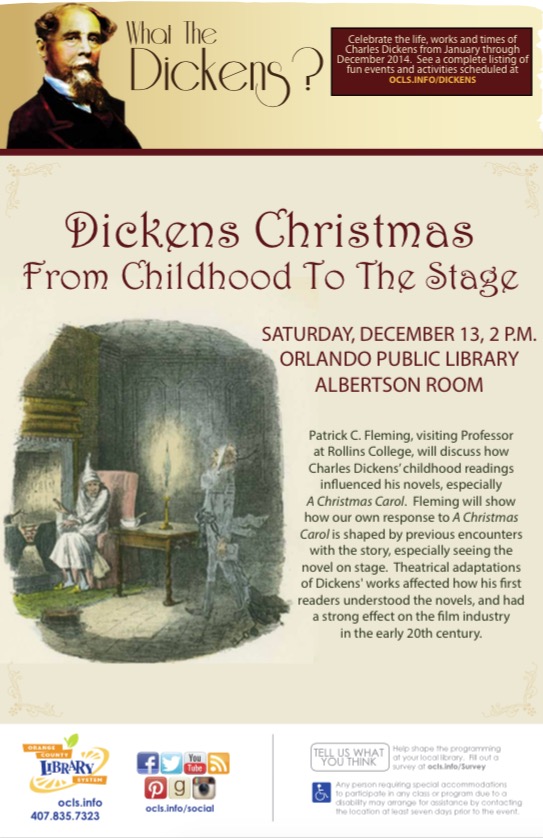

I’ll be doing that on Saturday: if you’re in Orlando, come hear my talk at the Orlando Public Library. I’ll be talking about Dickens, childhood, (both his own childhood and his child characters), and, of course, Christmas: