Alice’s Adventures in Google-Land

This year marks the sesquicentennial of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland — or, as it’s more typically referred to, Alice in Wonderland. I’ve been thinking a lot about the history and reception of the Alice books lately. This week I was pondering the two titles, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Alice in Wonderland. The difference matters. Google searches are an index to the popular lexis, and Google Image searches for the two titles look really different. This is immediately visible in the categories Google suggests:

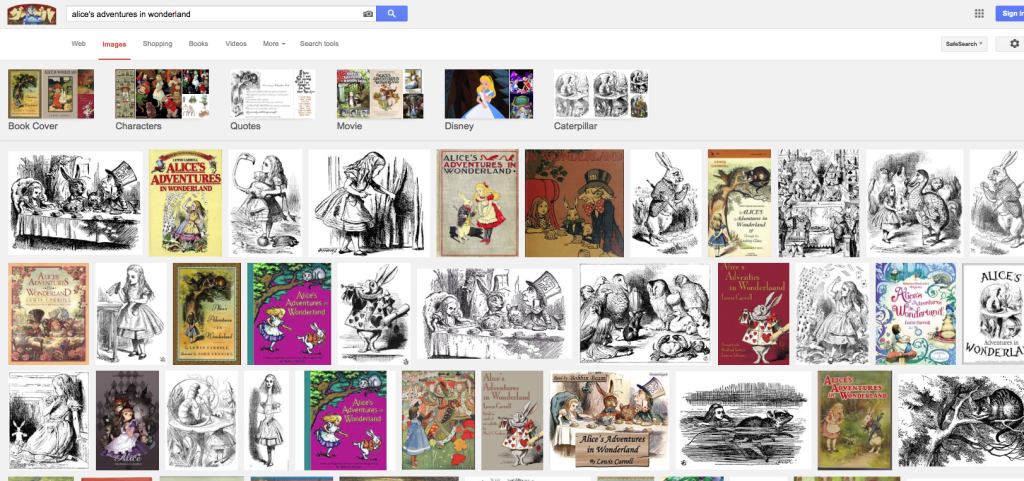

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is on the right. The first four categories are book covers, characters, quotes, and movies. The most prominent image for “characters” is Jessie Wilcox Smith’s 1923 illustration, and the top two movie posters are for the forgettable 1972 film, which starred Michael Crawford as the White Rabbit. If we look past the categories, we see a mix of book covers and the Tenniel drawings (click the picture to enlarge it):

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is on the right. The first four categories are book covers, characters, quotes, and movies. The most prominent image for “characters” is Jessie Wilcox Smith’s 1923 illustration, and the top two movie posters are for the forgettable 1972 film, which starred Michael Crawford as the White Rabbit. If we look past the categories, we see a mix of book covers and the Tenniel drawings (click the picture to enlarge it): Disney is recommended as a category, but doesn’t otherwise appear in the top images. Searching Alice in Wonderland, though, gives us something different (again, click the image to enlarge it):

Disney is recommended as a category, but doesn’t otherwise appear in the top images. Searching Alice in Wonderland, though, gives us something different (again, click the image to enlarge it):

The first two categories are “cast” and “Disney” (and the cast is not of 1972 film but of the 2010 Tim Burton one — produced by Disney). In this search “characters” pretty much means “characters as depicted in Disney’s 1951 cartoon,” an emphasis reflected in the costumes, too. Even the “drawings” category shows Disney’s, not Tenniel’s, and most of the images are from the Tim Burton film, with a smattering of Tenniel and of the 1951 cartoon.

Disney has pretty successfully appropriated Carroll’s text, and his adaptation arguably looms larger than Carroll’s in the popular imagination. Disney dominates the popular visuals for Alice in Wonderland, despite being essentially absent from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. So is Disney’s 1951 cartoon, Alice in Wonderland, responsible for the truncated title?

The short answer is no. Paramount’s 1933 film used the shortened title, and in their recent study of the publishing history of the Alice books, Zoe Jacques and Eugene Giddens note that the “diminutive version had circulated in the popular imagination almost since the original publication” (205). Their bibliography includes a 1903 film, Alice in Wonderland, though not until 1910 did a book use the truncation.

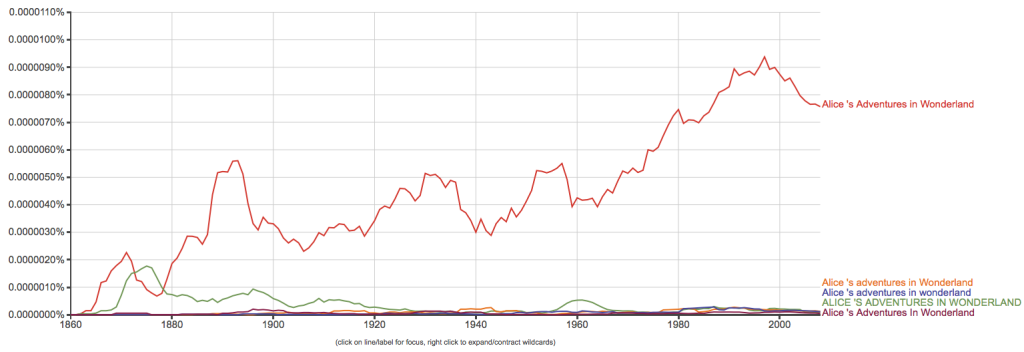

Just as Google’s search results give us some insight into the popular perception of the culture text, Google’s Ngram Viewer give us a broad historical picture. Ngrams chart the occurrence of words in the Google Books corpus. Here is the search for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland from 1860 to 2008:

As is typically the case with ngrams, the trends are easily explained. We see a sharp rise beginning with the initial publication, when reviews would have begun, then negative slope until the mid-1870s, when Looking-Glass bumped Wonderland back into the spotlight, and a sharp spike in the late 1880s, corresponding to Henry Saville Clarke’s popular stage production. The second rise corresponds to the first centenary of the book but is more likely explained by the adoption of Carroll’s text, with its references to size- and mind-altering substances, by the counter-culture of the 1960s (think Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” or the Beatles’ “I Am the Walrus”).

As is typically the case with ngrams, the trends are easily explained. We see a sharp rise beginning with the initial publication, when reviews would have begun, then negative slope until the mid-1870s, when Looking-Glass bumped Wonderland back into the spotlight, and a sharp spike in the late 1880s, corresponding to Henry Saville Clarke’s popular stage production. The second rise corresponds to the first centenary of the book but is more likely explained by the adoption of Carroll’s text, with its references to size- and mind-altering substances, by the counter-culture of the 1960s (think Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” or the Beatles’ “I Am the Walrus”).

Keeping in mind the difference in scale, here is the ngram for the truncated title:

The graph confirms Jacques and Giddens’s claim that the truncated title showed up pretty quickly. This graph differs from the above: it has a steadier rise, peaking in the mid-1930s, presumably with Paramount’s Alice in Wonderland (1933). The title got a slight bump during the war years, but the slope in the years following Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (1951) is negative, not picking up again until the 1960s. Disney’s film may now dominate the Google results for Alice in Wonderland, but the studio adopted rather than introduced the shortened title — and their cultural dominance doesn’t show up until later, at least not in the (admittedly limited) ngram results.

The graph confirms Jacques and Giddens’s claim that the truncated title showed up pretty quickly. This graph differs from the above: it has a steadier rise, peaking in the mid-1930s, presumably with Paramount’s Alice in Wonderland (1933). The title got a slight bump during the war years, but the slope in the years following Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (1951) is negative, not picking up again until the 1960s. Disney’s film may now dominate the Google results for Alice in Wonderland, but the studio adopted rather than introduced the shortened title — and their cultural dominance doesn’t show up until later, at least not in the (admittedly limited) ngram results.