Controversy and Wikipedia

This is the fourth in my series of posts about Wikipedia. I began with an overview and introduction, then wrote about Wikipedia and expertise. In my last post I discussed Wikipedia and universities.

Today I’ll look at some criticisms of the site. Some of the entries are themselves controversial: this PDF offers a “multilingual and geographical” analysis of the most disputed entries by looking at “edit wars,” situations in which editors change and revert each other’s edits to express different opinions on a topic. And because any one can edit it, the site is open to wiki-vandalism, a topic Nicholson Baker humorously discussed in NYRB. These site-specific disputes is interesting, but not the kind of controversy I mean.

Instead, I want to call attention to some ways in which Wikipedia has clashed with broad cultural values. An entire organization — Wikipediocracy — exists to, their website claims,

shine the light of scrutiny into the dark crevices of Wikipedia and its related projects; to examine the corruption there, along with its structural flaws; and to inoculate the unsuspecting public against the torrent of misinformation, defamation, and general nonsense that issues forth from one of the world’s most frequently visited websites.

It’s that last adjectival phrase, “word’s most frequently visited,” that causes all the fuss. Because Wikipedia is popular, it draws criticism from a range of directions. In this post I’ll discuss the site’s gender bias, the problems with entries about living persons (including “revenge editing” and fake identities) and whether a blog counts as evidence. Though I mention some instances from a few years ago, most of these “clashes” are from the last six months or so (a lot happened in April and May 2013).

As always, feedback is welcome: if you know of something even tangentially related to Wikipedia, especially if it would be of interest to undergraduates, please let me know!

Wikipedia’s Gender Bias

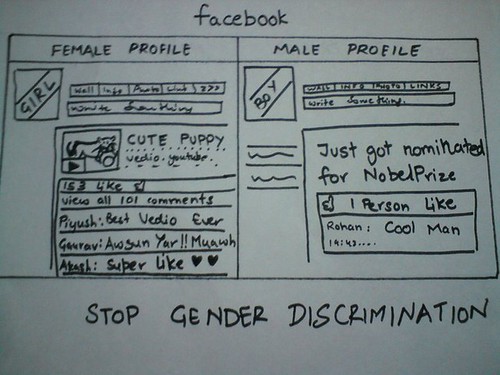

In April 2013, novelist Amanda Filipacchi published an op ed in the New York Times after she noticed that the Wikipedia page for “American Novelists” was being purged of all the women writers, who were being migrated to a separate (but of course not equal) page, “American Women Novelists.” The event sparked something of a firestorm, as it brought attention to a particularly egregious example of Wikipedia’s gender bias. This wasn’t the first time this bias was mentioned, or even the first time the New York Times had written about it. Back in 2011 Noam Cohen wrote about a survey showing only 13% of Wikipedia contributors are women. Things actually got worse by 2012, when 9 out of 10 Wikipedians continued to be male.

One could provide any number of discrepancies in coverage that result from this gender divide: Cohen gives the example of Mexican feminist writers (a category with 5 entries when he wrote; 8 as of 8/1/2013) vs. 45 pages about characters from The Simpsons. Nathalie Collida and Andreas Kolbe wrote a comprehensive response to the Filipacchi incident for Wikipediocracy, providing even more examples. And Claire Potter, in a well-titled Chronicle article, Prikipedia? Or, Looking for the Women on Wikipedia, puts the encyclopedia in the context of other online happenings, like facebook (women  overtook men in 2009) or Twitter (more women, as of 2012) or Digital Humanities (roughly equally split), and wonders why Wikipedia hasn’t caught up.

overtook men in 2009) or Twitter (more women, as of 2012) or Digital Humanities (roughly equally split), and wonders why Wikipedia hasn’t caught up.

Potter mentions Sarah Stierch, who in 2012 organized “She blinded me with science”, a Wikipedia meet-up to improve the coverage of women scientists. Following Filipacchi’s op-ed a number of people mobilized to put together similar events. At HASTAC Adrianne Wadewitz wrote about the need for academics to address the gender gap, and edit-a-thons were organized under Twitter hashtags like #tooFEW and #GWWI (Global Women Wikipedia Write-In), and promoted in the Chronicle. These projects are continuing.

Wikipedia and Living Persons

One thing that distinguishes Wikipedia from other encyclopedias is its coverage of living persons. It has the advantage of speed: in February I posted about the speed at which Daniel Day-Lewis’s page was updated after he won the Best Picture Oscar. But there are costs. Back in 2005, retired journalist John Seigenthaler complained in USA Today that his Wikipedia page erroneously linked him to the Kennedy assassinations. Presumably this was somebody’s idea of a joke, but the “fact” was up there for several months. And in 2012 Philip Roth wrote an open letter to Wikipedia in the New Yorker, in which he chronicled his experience trying to correct an error in his Wikipedia page: because the site requires “secondary sources” and prohibits people from editing their own page, Roth needed a citable source to clear things up (hence the letter).

The Seigenthaler affair notwithstanding, these are minor events, perhaps even humorous. Ira Matetsky, a New York City lawyer who’s also a Wikipedia administrator and member of the arbitration committee, explores more troubling terrain in a series of posts for The Volokh Conspiracy, a group blog written mostly by law professors. Matetsky writes insightfully about the “biography problem,” especially as it relates to the privacy of non-public persons. He gives the example of a 13-year old boy who had been kidnapped and tortured: Wikipedia briefly included personal details in an entry about the victim (whose name still appears in a Wikipedia entry about the criminal). This is a particularly disturbing example, but it’s not without precedent. It’s not the very public figures who have to worry about their Wikipedia pages — people like Barack Obama and George W. Bush have Wikipedians from all sides continually watching their pages. It’s the “somewhat notable,” whose pages might be visited only rarely, who should worry, since errors (or slander, or just unwanted invasions of privacy) are less likely to be noticed and fixed. Matetsky discusses some of the Wikipedia policies implemented to fight such battles, including flagged and protected or semi-protected articles.

Revenge Editing

Closely related to these issues is a practice for which Wikipedia has its own lingo: “revenge editing,” the altering of another person’s entry just out of spite. This practice got national press after Amanda Filipacchi’s Wikipedia page was vandalized following her New York  Times article (see above). Andrew Leonard responded, claiming that Wikipedia’s lust for revenge was maybe even a bigger problem than it’s sexism. If you’ve got some time, read Leonard’s follow-up Salon article about this practice, and especially about the Wikipedia editor “Qworty,” who is probably novelist Robert Clark Young. Leonard gets some help from Wikipediocracy, and the story he tells really is wonderful, and raises some serious questions about how the real world interacts with Wikipedia. In its publicity, the “Qworty” episode recalls an earlier Wikipedia controversy, which gained public attention after Stacy Schiff’s 2006 New Yorker article. A user calling himself “Essjay” claimed in his Wikipedia profile to be tenured professor of religion. He rose high in the Wikipedia ranks, becoming a member of the arbitration committee and a paid employee of Wikia. He turned out to be a 24-year old community college dropout with no qualifications. Whether claims about credentials matter to an encyclopedia anyone can edit depends a lot on your point of view (see my previous post about expertise), but it certainly raised questions of honesty and integrity. An editor’s note was added to Schiff’s article (in the print version, it appeared in the section The Mail), the fallout was covered in the New York Times, and Wikipedia devotes a rather detailed entry to the whole affair.

Times article (see above). Andrew Leonard responded, claiming that Wikipedia’s lust for revenge was maybe even a bigger problem than it’s sexism. If you’ve got some time, read Leonard’s follow-up Salon article about this practice, and especially about the Wikipedia editor “Qworty,” who is probably novelist Robert Clark Young. Leonard gets some help from Wikipediocracy, and the story he tells really is wonderful, and raises some serious questions about how the real world interacts with Wikipedia. In its publicity, the “Qworty” episode recalls an earlier Wikipedia controversy, which gained public attention after Stacy Schiff’s 2006 New Yorker article. A user calling himself “Essjay” claimed in his Wikipedia profile to be tenured professor of religion. He rose high in the Wikipedia ranks, becoming a member of the arbitration committee and a paid employee of Wikia. He turned out to be a 24-year old community college dropout with no qualifications. Whether claims about credentials matter to an encyclopedia anyone can edit depends a lot on your point of view (see my previous post about expertise), but it certainly raised questions of honesty and integrity. An editor’s note was added to Schiff’s article (in the print version, it appeared in the section The Mail), the fallout was covered in the New York Times, and Wikipedia devotes a rather detailed entry to the whole affair.

What Counts as Evidence?

In June 2012, Benjamin Wittes and Stephanie Leutert, who maintain the Lawfare blog, tried improving the Wikipedia entry for “lawfare.” They cited the blog, but their edits were removed within minutes. The editors claimed that an unedited blog was not a reliable source, a claim which may or may not be consistent with Wikipedia’s guidelines. These anonymous Wikipedians maintained that if Wittes and Leutert’s entries were so important, they would be published somewhere else, not just on a blog. On the face of it this is not an unreasonable assumption, but Wittes and Leutert argue that such a policy seems increasingly outdated and, ironically, inimical to our current digital, global environment — the very environment that allows for Wikipedia in the first place. They conclude their article in Harvard Law School’s National Security Journal,

Wikipedia, an experiment in new media that has succeeded beyond anyone’s imagination, is so prejudiced against new media … As publication outlets proliferate in an era of rapidly-developing communications technology, these policies—to the extent they are followed—all but guarantee that Wikipedia will fall behind the conversation.

As an intentional final twist, they made the same edits to Wikipedia’s “lawfare” page that they’d made before, but this time cited their own article in the Harvard journal. Other than a sentence in the lead paragraph (which gets its own section in the talk page, referring to Wittes and Leutert as “jilted bloggers”) the edits seem mostly removed.

The “lawfare” incident brings me full circle, to Mark Bernstein’s comments, which I mentioned in my first post. Bernstein begins with the Filipacchi affair, and laments the problem of revenge editing. But like Wittes and Leutert, he ultimately concludes that the major problem is structural, rather than purely cultural. And he’s pessimistic about the site’s future:

I think Wikipedia’s about over. To say, “some of this book’s footnotes are just links to Wikipedia articles” is universally understood to be withering. We don’t edit Wikipedia anymore. We don’t consult it for things that matter. It’s merely a good resource for finding odd facts no one cares much about.

This fall I’m teaching a course about Wikipedia, so I obviously care about it. But I’m an academic, and my scholarly interests are historical. Will Wikipedia perish, or survive merely as a relic of the first decade of the 21st century? Or will it continue to be one of the most important sites on the Internet?

What do you think?

And yet several months after wikipedia contributors have been exposed for creepy behaviour towards children, those contributors are banned from wikipedia either by the Arbitration Committee, or the WMF.

Journalists discover many images of naked children, including those taken with a Nintendo 3DS

http://www.buzzfeed.com/jackstuef/its-almost-impossible-to-get-kiddie-porn-off-wiki

Earlier this year the bloodied photo of a child rape victims genitalia was being bandied about Commons. Last year a convicted child porn distributor was defended on Commons for 10 days until the issue raged on Jimmy Wales page for a week, and the WMF eventually got off their arses and globally banned the account.

Really? That’s it? Considering how worked up you and everyone else on Wikipediocarcy get about relatively minor ‘problems’ on Wikipedia, things that no matter how many times you beg and plead, distort and lie, no reliable, reputable and trustworthy source has ever or will ever take notice of, this attempt to downplay the very real dangers Wikipediocracy represents to ordinary people was supremely ironic.

At the end of the day, whenever someone decides to take notice of what actually happens on your supposedly insignficant forum, then whether or not that makes it into Wikipedia will be the least of your concerns. What are the FBI and the NY Times going to be more interested in after all? Is it spurious complaints repeated ad nauseum on your forum about ‘child porn on Commons’, or is it when someone kills themself after being wrongly named by your forum as a pedophile, with all the consequences that brings. America has many freedoms, but even they recognise online threats and harassment of the sort hosted on your forum for what they are, namely criminal behaviour. And for the record, Wikipediocracy is as popular as a webforum as Citizendum was as an encyclopedia.

And yes, I’m still anonymous. Sorry if that upsets you, leaving as it does the only avenue of actually addressing the charges by way of reply rather than targeting me, but given who you are and what you do, I’d sooner give my credit card details to a Ukranian gangster than tell you even my first name.

Whatever you say, MickMacNee.

Avalanche of lawsuits? Who do you think you’re kidding with this nonsense? If that were the case, then if even 10% of the garbage you write about Wikipedia and its contributors was remotely accurate or honest, it would surely have ceased to exist years ago. This is just another example of how you live in your own little bubble of half-truths and hate, totally impervious to reality.

In the real world, Amanda Filipacchi blogged about how she was addicted to reading the gossip on Wikipediocracy, to the point it was damaging her health and work. In your world, that is an endorsement or an affiliation. Lunacy.

In the real world, Larry Sanger is the buffoon who created the total failure that is Citizendium, and wastes FBI time with spurious complaints about child porn on Commons. In your world, he’s a man whose opinion is to be respected. Sure.

In your world, Kevin Morris and Andrew Leonard are “reporters”. That one can just be left there, it’s totally laughable all on its own. Except to state the obvious – there isn’t a single reputable journalist who has ever gone within a hundred miles of any of your half-baked claims, or would ever risk their reputation by even mentioning Wikipediocracy in one of their articles.

Despite all your half truths and diversions Greg, the fact remains, Wikipediocracy is a dangerous site, because it routinely does dangerous things like baselessly accuse people of being pedophiles and allow *anonymous* people to make *anonymous* threats of physical violence and other real world consequences against people whose identities have been exposed and disseminated through the site. And you have the gaul to express wonder at why people like me don’t give you their real names? Amazing.

How sad that you think criticising my grammar is more important than defending your site against some pretty serious charges. But then again, that’s all you can do, because you know fine well that on those charges, you are as guilty as the day is long.

Obvious troll is trolling. Mildly humorous how you elect to belittle the accomplishments of four different people (by name) who are obviously more successful than you ever will be, in your feeble (anonymous) attempt to critique a web forum. A web forum. Really? You’re that worked up over a modestly popular web message board? If Wikipediocracy is so dangerous and evil, get Wikipedia to say that about it, since you believe Wikipedia to be the true and perfect reference resource. That should keep you busy and out of trouble for a few weeks.

Anonymous is demonstrating his skills as a Wikipedian, burying posts under his own. There are no real debates at Wikipedia, only shouting. We should thank him for the demo.

Wikipedia is a small town with the vices of a big city and that makes it a great subject for study and a community best avoided. Like a prison. The inmates can produce some useful material if the tasks are kept simple but they often use it to smuggle illicit messages in and out. Much of the smuggling can seem petty but the scale of the activity should make it influential over a long time. The wardens rely on informants to help them keep control of the inmates but they then become complicit in much of the injustice that goes on there. It is an unholy mess. Various kinds of rape are practised by the community. Why else do women avoid the place?

FYI, Wikipediocracy is a very dangerous site. While some might like to see it promoted as having lofty and moral aims, the reality is quite different. In both its blog posts and the forum, its owners think nothing of having their site used as a platform for insinuating named people are pedophiles or curators of child porn. They think nothing of allowing it to be used as a host for threats of physical violence or other damaging real world consequences if their targets don’t do their bidding. The whole irony about Wikipediocary is that many of the flaws in Wikipedia that it complains about, such as anonymous revenge postings, harassment/threats, libel/defamation, can all be found there too. Unlike Wikipedia though, it’s not an unfortunate side effect of the environment/system, it’s a core feature. Wikipediocracy,com is the very definition of a revenge site. You won’t find anyone behind or deeply involved in it that can be remotely described as a investigative journalist or any kind of credible internet activist of the sort you’d find at other more reputable organisations. It’s backers and major contributors are by and large not people with high moral drives, they are simply a loose collective of people with a common goal – a simple desire to act on the various grudges they hold against Wikipedia, with the according lack of quality or objectivity to anything it produces. A secondary irony is the lengths certain Wikipediocracy members have gone to to ensure they have an article on Wikipedia that inflates their significance and importance far far beyond what reliable sources actually support, and which reads much more like an advertisement or promotional piece than some of the best ‘paid for’ articles on there. That’s strange behavour for people who spend the rest of their time carping on about how Wikipedia is easily abused by cabals of self-interest groups. Would you find someone at a reputable and moral internet activism organisation spending any time abusing Wikipedia in this manner? Of course not. But then you wouldn’t also find them hosting threats and insinuations about pedophilia on their sites either.

Note that the person describing Wikipediocracy as “very dangerous” casts these aspersions from behind a cloak of anonymity, as is typical with most who oppose the site. If Wikipediocracy were such the hive of owners who “think nothing” of false accusations and libel, then where, pray tell, is the avalanche of lawsuits that would surely befall such a site? Yes, Wikipedia has an article about Wikipediocracy, but there is nothing there to support this spurious claim that it’s a dangerous site, because it’s not. As far as I know, the Wikipedia editor who created the article about Wikipediocracy has no affiliation with the site. You do see implied endorsements of Wikipediocracy by reporters Kevin Morris and Andrew Leonard, as well as by novelist Amanda Filipacchi. Not to mention, Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger has been a repeated contributor to Wikipediocracy. All of this seems to offend “Anonymous” above, but any sane person would have a difficult time seeing why these reputable professionals would risk endorsement of and affiliation with a site that was truly “dangerous”.

No, here we have this paranoid, hand-waving warning about Wikipediocracy, left by someone who uses grammar like “a investigative” and “it’s backers”, unwilling to sign their name to their outlandish opinion. How sad. How typical.

I can confirm that Wikipediocracy is extremely dangerous, for Wikipedia !

Very interesting !

Sir:

For your information, two Wikipediocracy members and longtime Wikipedia critics are presently writing a book about Wikipedia’s history and internal problems — Edward Buckner, a philosophy instructor, and myself. We have assembled a private database of information about Wikipedia’s insider community and some of their innumerable dirty tricks. It is approaching TWENTY MEGABYTES of text.

http://www.logicmuseum.com/x/

If you would like to know more, please contact me for help.

Thank you! Ed sent me the samples, which look very interesting. I’ll keep an eye out for the book.

Regarding vandalism of the biographies of living persons, your readers and your class may be interested in a study that I coordinated — to examine 3 months’ worth of edits to the 50 Wikipedia articles about US senators, to see how often they were vandalized, and to judge how long it took Wikipedia to repair the damage.

http://www.mywikibiz.com/Wikipedia_Vandalism_Study

In more cases than you might imagine, the damage was sinister, and it lasted for days and weeks, not minutes.

Thanks Greg! That study looks interesting. I’ll share it with students, especially as some might be interested in politics and the implications of your results.

Regarding Qworty cleanup. A handful of wikipedia editors made an effort to collate all the articles that Qworty touched and looked a few of them, but the effort ceased soon afterwards.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Contributor_clean-up/Qworty

This is not surprising as the same thing happened with Jagged85, a far more prolific contributor to the site, who frequently prevailed over subject experts due to being regarded as one of the more respected editors. Jagged85 edited articles in Mathematics, History, Physics, Astronomy, Medicine, Literature, and Philosophy, his main focus was to remove Western European antecedence in a subject and replace it with a non-western antecedence. Often the citation he gave either did not exist, did not support the claim being made, or flatly refuted the claim being made. Jagged85 managed to insert entirely fictional elements into articles such as avicennian logic:

http://ocham.blogspot.co.uk/2010/06/avicennian-logic.html

and when discovered doing so in 2010 was allowed to continue making contributions to wikipedia until further discovered to be falsifying articles on “Video Games” at which point he was banned. In 2010 a project was started to clean up the Jagged85 contributions, some thought that the issues were so serious, and ingrained into the current articles that the only recourse should be to stub the articles and start again. However, when the articles in question include “Number Theory” such removal was considered to be too great a recognition that the ‘encyclopedia” was compromised. Again a list of the 1000s of edits were made, but the effort to fix the problem stopped shortly after. Wikipedia contributors have a very short attention span.

Addendum: Jagged85 was allowed to edit a further 3800 pages from the time that he was discovered falsifying articles until his eventual ban. The extent of the problem is listed here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Requests_for_comment/Jagged_85

the discussion about the falsification here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Requests_for_comment/Jagged_85

and the discussion about the progress of the cleanup here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia_talk:Requests_for_comment/Jagged_85